![]() Joseph Appleyard's Methods of a Sporting Painter

Joseph Appleyard's Methods of a Sporting Painter ![]()

"It is my intention to give a

brief explanation of the methods adopted by the sporting painter of

today,

which may in some measure enlighten other readers of the Artists who

are interested in country sports as a subject for their

expression."

Quote from Joe's Methods of a

Sporting Artist, which I believe was published in Yorkshire Illustrated

and is featured below as an Additional Chapter

The reverse side of this painting hosts a hardboard Subbuteo Pitch

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER ONE | - The Thrill |

| CHAPTER TWO | - Methods of a Sporting Painter |

| CHAPTER THREE | - Missing |

| CHAPTER FOUR | - Missing |

| CHAPTER FIVE | - Missing |

| ADDITIONAL CHAPTER | - Painting a Sporting Scene with the Vale of Lune Harriers |

The Thrill

I am often asked if I use photographs in the execution of a sporting painting. Although I have never made a practice of it, I do not see why they should not be used, providing they are utilised for detailed work only, or to obtain portraits of other members of the field.

When collecting material for a racing incident I find it a good idea to go to the actual race meeting with sketchbook, pen and pencil. Sketch as much of the afternoon's activities as your time will allow. Horses, owners, trainers and jockeys in the paddock, the preliminary canter to the post, the start and finish of races, bookmakers and their stalls, the racing crowd in general. Do not do any drawing of starting gates, number boards, grand stands, or other static subject matter. All these can be sketched at leisure on a non-racing day and much time can be taken in obtaining accurate renderings. These can then be saved for future times when doing paintings of that particular racecourse.

The method of making working drawings of horses, jockeys and trainers is on the same lines as the ones used for the hunting scene.

Thoroughbred horses of course vary from the hunter, the jockeys seat in the saddle is much different from that of the hunting man, but as mentioned at the beginning, if the artist knows the technical side of the sport, these observations will be counted for.

A day at a training establishment can be most enjoyable for the artist, but he must bear in mind do not thrust himself unduly onto any member of the staff. If he is sketching any particular racehorses he should do it with all possible speed, as thoroughbreds are a highly sensitive breed and are prone to colds if stood too long.

Should the artist be doing a more careful study in watercolours, he should do this just inside the door of the horse's loose box. In fact many good paintings have been done from time to time in the mellow light of a stable interior.

Spend an early morning sometime with your sketchbook, watching horses doing their gallops and exercises A fund of material can be gleaned from such a visit. It is at a time like this when the artist can study the movement of horses and riders in action. Try to keep your sketching lines down to a bare minimum, the fewer the lines, the better the action. Throw yourself into the excitement of the scene and as you sketch you should have fairly good results to show on your paper.

Cart Horse Parades and Agricultural Shows prove ideal places for colour work. One decorative team of horses with a brightly painted cart can be a sufficient urge to get your paint box operating.

You can do quick colour sketches whilst the competitors are awaiting their turn for judging.

The parade as a whole for a finished picture would indeed put the best man on his mettle, if he were to put down the onlookers as well as the gaily-decorated horses.

Given a good day's weather, I think there is nothing more enjoyable than painting at an agricultural show. Perhaps some half rugged farm horses tethered to a fence under the shade of a tree, or a cow being groomed in preparation for the show ring, in fact any of the activities which occur in the numerous animal classes as they await their turn for exhibition and judging.

Finally I would say, keep the sketchbook in operation at all times. Be as free and easy in your style of drawing and painting on every occasion.

Not only will you enjoy

this type of sketching . . . . . . . . . . . . this is where Joe' script

peters out!

![]()

Ever since the reign of James 1st, sporting painting in England has been in evidence. The names of many famous painters too, has emerged from this branch of art, which, from the middle of the 18th century to the latter end of the 19th century showed signs of the sporting artist being much in demand.

This of course was to the popularity of the horse and hound in support; cock-fighting, shooting, riding and coaching also played a big part in the many outdoor recreations of the country squires and gentlemen of that period. Therefore, it is not in the least surprising that the sporting artist had, helped with his landscape backgrounds, plenty of subject material to introduce his pictures.

Landscape was of course just as important as the animals and figures and to see the best examples one has only to look at any of the works by George Stubbs, Ben Marshall and John Ferneley to mention only a few of the first rank.

A lot could be written about sporting painters and painting of the past, but this has been done most admirably by such writers and authorities as the late Sir Walter Gilbey, Major Guy Paget, Walter Shaw-Sparrow and others.

It would seem that with the horse fast disappearing from the roads, much of the interest of the animal painter would have gone with it. But luckily that is not the case, because we still have our own country pursuits introducing to us, as of old, horse and hound in the form of hunting, racing, coursing, horse-shows, agricultural shows and in the industrial areas we have cart horse parades, greyhound racing and dog shows.

How then, does the artist attempt his paintings, which if well done, have such an immediate appeal to the sportsman?

It is my intention to give a brief explanation of the methods adopted by the sporting painter of today, which may in some measure enlighten other readers of the Artist who are interested in country sports as a subject for their expression.

Firstly I should say that he must know his subject well and attend as many sports meetings as he can. This he will do of his own natural tendency if he loves the sport.

The quick sketching of animals and figures in movement should also be one of his chief assets, without which much will be lost.

He should be of the open air type and be able to work out of doors even in the most adverse of weathers.

Here again a great deal of his sketching will be done on the spot at hunt meets and on the covert side during the hunting season.

Even on a cold day, being well wrapped up and absorbed in sketching the cold will hardly be felt.

The most annoying of the elements are wind and rain, in which case be procedure of sketching seems well nigh impossible, unless cramped up in a car.

Mittens or gloves could be worn to keep the hands warm, but I have never used either, as I find them rather clumsy. Admittedly on many occasions my hands have been almost blue with cold by the time I have done a few odd sketches, but I have managed to keep the circulation going by rubbing my hands vigorously.

During the summer months it is more comfortable, but I prefer winter sketching when I think nature provides a more infinite variety of colours in the landscape.

I find that following the hunt on foot provides better opportunities for sketching than when mounted.

In the latter case I can enjoy the sport and rely a lot on memory for my sketches, immediately after the hunt.

Memory drawing is essential. Nearly all the works by the late Joseph Crawhall were memorised and Lionel Edwards relies a great deal on it, without which I do not think he could give us the fresh colour and spontaneous action of his hunting and racing scenes.

The anatomy of animals should be studied, coupled with drawing animals from life. A good book of the subject being " Animal Painting and Anatomy " by Frank W. Calderon. Plenty of landscape practice and the study of old masters of landscape and sporting painting should be observed.

The approach to the actual sketching and painting should be a personal one. There should be no hard and fast rules which might interfere with the originality and style of the individual concerned.

It will however be helpful, to give a few hints which will be of advantage to the beginner.

A sketch book with stiff backs and pages of smooth notepaper surface should be obtained, the size being optional. The one I use is 12" x 9", a "poachers pocket " inside my jacket lining being made to hold it when not in use.

Two pencils, an HB, a 3B and a ball-point pen completes my equipment on an outing for preliminary sketches at such times when colour work is not desired.

On arrival at the appointed place, whether it be a hunt meet or agricultural show, the artist [if he has a painting or commissioned work in mind] must have a rough idea as to what models he will choose as subjects for the painting.

On the other hand, occasions arise when the artist attends a meet or show, purely to sketch for his own pleasure, or to increase his knowledge. In some cases it is to supplement his collection of reference sketches.

For animals and figures use the 3B pencil. Hold it tightly and sketch freely, letting your hand glide over the smooth page. Put down what you see and the memorising of action, will work its way into your work. Rarely should a rubber be used. If a mistake is made, let the faulty line remain and try to build a corrective line near it.

It is by doing this that a freedom of line and looseness of style will be accomplished. This is most desirable if one wishes to create "movement " in the sketch.

The ball-point pen is also used for quick sketching and is a change from drawing in pencil.

The HB pencil comes in useful for detailed work such as drawings of riding equipment, bridles, bits and the like.

It is handy too for small background landscapes and adjusts itself to buildings and trees in detail where a fine line is often necessary for an accurate rendering.

Make as many sketches as you can, where and whenever possible. Build up a small collection which can be used from time to time in the sporting pictures which will eventually come from your brush, either in oils or watercolours.

When the sporting artist gets a commission to paint an incident, say in the hunting field, the patron usually states what he has in mind, with the favourite horses, hounds and hunt followers which he would like featured.

A discussion with the artist makes things clearer, he, giving his suggestions and perhaps asking his patron what would be a suitable place to visit to get a scene for the background of the proposed painting. When both have agreed on the form which the painting should take, the artist can then give an appropriate price for such work in oils or watercolours.

The decision is then left to be patron, who, shall we say in this case, chooses a watercolour.

Permission should then be asked to sketch at the kennels, stables and other places involved for the artist's subject matter.

This is usually arranged with the patron, phoning the hunt secretary or people concerned, saying that an artist will be calling that the kennels and stables on a non-hunting day to make sketches.

In the meantime the artist we will assume is still attending hunt meets in his district and is usually well informed as to the appearance and names of the more popular members of the field. This will be of advantage.

Let us imagine that the painting will show the huntsman in full cry with his hounds, followed in the middle distance by the patron and a group of other members of the hunt.

You will know doubt have seen this incident many times and be acquainted with the characteristics of the huntsman, how he seeks his horse, handles the reins and encourages the hounds.

The first step I would advise is to get all your working drawings done at the kennels.

Ring the huntsman on the phone and tell him what time you hope to arrive. In nine cases out of ten a professional huntsman is a most obliging person and will be ready for you on arrival.

Take with you a light telescopic easel, watercolours, dipper brushes, pencil, pen, a small pot of white poster colour, paint rag, light drawing board, half a dozen sheets of gray toned paper and your sketch book.

On arrival at the kennels, tell the huntsman that you would like to see the pack of hounds as a whole.

He will no doubt assemble them for you in a grass paddock. Stand and observe them for about five minutes, chat about them with the huntsman, ask questions and you will find him most enthusiastic and pleased that you too, are as interested in them as he himself. Do not make sketches at this point. You will gradually attune yourself to the general colour and stamp of the hounds.

For the methods of painting I can do no better than to describe an actual incident which took place at the kennels of a local hunt on one of my recent visits.

After seeing the pack as a whole, the best eight hounds were singled out by the huntsman and the whipper-in also present at the time, drew them from the pack and took them into an enclosed yard. These eight then, were to be the leading hounds and to be featured in the foreground of my painting.

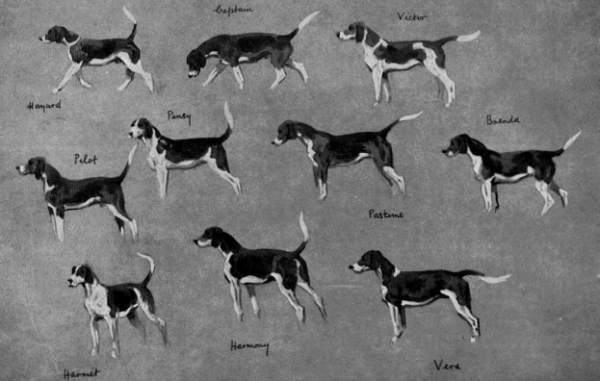

The next method is to have these chosen hounds running and snooping around. I then observe more keenly, the build, pattern, character and action of each hound. When satisfied, I fix up my easel in the adjoining sheltered yard, placing a sheet of light gray toned paper on the drawing board. Making sure that I have made my dipper of water secure and placing my watercolour box in a handy position, I beckon to the huntsman to bring in the first hound. The hound dashes in, full of spirit and energy, " Hazard " is his name, a nicely patterned black, tan and white specimen of this pack.

I then sketch him freely and quickly on to the paper using the ball-point pen. After much dashing around, [and even much more coaxing by the huntsman to get the hound to stand in profile ) the outline is eventually finished.

My watercolours then come into play and rapidly I wash an ochre over the whole drawing of the hound. Whilst this is still damp I paint in the tan colour, then with a little cobalt and black mixed, put in the shadows to help model the hound. Then follows the painting of the black markings and I finish the painting with the white parts, using the white poster colour, slightly toned with ochre from the paint box.

"Hazard " is then put back into the kennel and the next hound to be portrayed is brought in.

This is a fine bitch hound with the fair name of "Pansy ". The same sketching and painting process is repeated and so on through the series of eight, "Pilot ", "Harmony ", "Brenda ", "Harriet ", " Captain " and "Pastime ".

The period of sketching the eight hounds is roughly about two hours.

The next working drawings are of the huntsman and his horse.

Back in the huntsman' s house, whilst the huntsman is changing into his scarlet coat, his wife serves a welcome cup of tea and biscuits.

The huntsman then takes me to the stables where his horse is kept. It is a rather large, common looking chestnut mare by the name of Miss Parry.

The stable lad is given instructions to take off the rug and lead the mare out into the yard.

I then ask the huntsman to mount and pose, making sure that he is in a natural, relaxed position and not sitting bolt upright and stiff which is customary when a rider poses for artist or photographer.

I put another sheet of gray paper on the board and place it on the easel, making a point of not being too near my models. I take up a position about four yards from them on the near side of the horse.

At the moment I am not interested in the horse, but the position and colour of the huntsman.

I sketch in on the paper with the pen and try as much as the small area of space will allow, to get something of a facial likeness. Personally I find this my most difficult task, but having a knowledge of the huntsman's character helps a lot in getting most of his likeness in the sketch.

Taking up the watercolours I start on his face and then take any other part to follow on, say jacket, breaches and boots and finish with the cap and gloves.

When sketching your huntsman, note whether he has a tendency to lean either in a forward or backward position. Note how the cap is placed on the head, how he holds his hunting crop and reins, the position of his boot in the stirrup-iron, and how the scarlet coat " swings " over the back of the horse and many other details, which your patron is bound to look for.

Written notes of any small detail will also prove useful for studio work.

When the painting is finished I get the huntsman to ride round the yard and with sketch book and 3B pencil make quick notes of the horse and rider in motion.

Finally he poses again, this time for about fifteen or twenty minutes whilst I do a pencil sketch of himself and the horse - this being to ensure correct proportion of horse and rider.

Usually there are two whippers-in to a pack of hounds. I ask the huntsman if he will get the first one to pose for me on his own horse.

This sketch is only done in pencil in the sketch book, with written colour notes, because no doubt, he will be in the distance on the finished painting.

I usually sketch the second whipper-in also, as a matter of routine, why leave him out? Ten to one at some time or other this sketch will be required.

I can now let the huntsman and his staff resume their normal duties whilst I concentrate on the huntsman's mare.

As the groom holds her I make a good pencil sketch of the head and bridle. When doing this I watch for the prick of the ears, or in fewer cases the lop of the ears (I think lop-eared horses are characters in themselves) and if a horse has this failing, portray it and you will capture a good deal of his portrait.

Make sure the horse is hunted in the same type of bridle and bit as you are sketching.

Make a special drawing of the bridle as needs be, it will be well worth the time taken.

I make close-up drawings of the legs, the body and tail. How the mare "carries " her tail is a feature to be looked for, these drawings are indispensable when doing the finished painting, moreso, it is should be a portrait of a standing horse.

When these drawings have been done in the sketch book, I return to the easel with a fresh sheet of gray paper on the board. At the same distance as in the first case I take up my position (I should mention that in my opinion, it is always best to stand at the easel, which enables more freedom of movement.)

I draw the horse with pen or pencil and when this is done start to use the watercolours. A very faint wash of cobalt blue is painted over the whole horse. When it is about dry the chestnut coat is applied. For this I use with a variety of mixings, light red, burnt sienna and yellow ochre.

The darks being made up of crimson, ultramarine and sepia.

The white markings of the mare's blaze on her face and the four white " stockings " being put in with body colour.

The sketching of the huntsman, whipper-in and horses as stated above completes the artist's day.

By now it is late afternoon and the sun is going down. There is a chill in the air and the artist shivers a little. He has visions of a well earned meal in a warm dining room. With these thoughts, he takes his sketches and puts them into his portfolio, takes down his easel and packs his belongings into his ruc-sac, well satisfied with his day's work.

In taking leaves of the huntsman and his staff thank them for their help, they appreciate this and you can be sure you will be made welcome on any further visit.

The following day finds me working on small sketches from the life, in watercolours, of my patron, his horse and other members of the hunt and their horses who are to be included in the landscape of the finished painting.

The procedure is a repetition of the previous day's work at the kennels, but the sketches are made much small. Perhaps a visit to three or four residences to get this information then completes the set of drawings as far as figures and animals is concerned. Only the landscape has now to be done.

I like to spend a day on this, which I must admit I find most enjoyable. The best time to do the landscapes (usually two versions being done of the same spot) takes from say 11 a.m. to about two-thirty in the afternoon.

The size of the sheet used in each case is approximately 12" x 8" and again is either gray in tone, or the dark buff David Cox paper.

Drawing in carefully the outlines of the landscape takes about ten minutes. Watch closely, the sky, which will make or mar your painting.

Wash it in quickly using a full flowing brush, observing the tone and shape of the clouds.

Try to get as good an impression in the shortest of time. Do not pause, or even "work up " your sky effects. First clean impressions are usually the best and I am reminded now as I write on this subject, of the grand effects obtained by Lionel Edwards. His skies are done so spontaneously, always fresh and full of the atmosphere of that particular hunting day.

When the sky is almost dry on the sky line of your sketch, put in the distant background.

The dampness at the bottom of sky wash will help to give a soft hazy appearance and will help to keep the distance well back.

Follow this up with the broad strokes of the brush for the tone of the middle distance and finish off with these broad washes as you get lower down until you eventually finish off with the foreground.

Apply the distant trees, hedges and other natural detail when the sketch is again almost dry.

The middle distance objects and foreground being put in when the sketch is dry.

A point to observe is that you allow plenty of space in which to place your hounds, horses and riders.

This I cannot stress too much; failure to do so will result in overcrowding. When the first sketch is completed, I move my position to another part of the field, bearing in mind all the time, how the hounds will run in the final painting. Usually by the time I start this second painting the sky has changed considerably. I again take advantage of this and repeat the same methods of sketching on similar lines to the first.

Finally I use my sketch book and draw carefully any tree, fence, or group of buildings, which may turn out to be a main feature of the landscape.

This now completes all the working sketches and a start on the finished painting can be made in the studio.

When starting the finished painting you need a sheet of toned paper (preferred gray) ingres is a good paper and takes a good wash, besides having a nice ribbed texture. Failing this a sheet of David Cox paper is also ideal.

The size of the paper is left to your own discretion but I find that a surface of approximately 22" x 16" plenty large enough.

Stretch the paper on a strong drawing board and when ready place on the easel.

Now get all your working drawings together. You will need the two landscape sketches first and the sketches in your book.

On a separate sheet of white cartridge paper, with your 3B pencil draft out some compositions of your picture. Spend a little time over this. They need not be big sketches, say about 4" x 3". Do about half a dozen, moving the animals and figures about on each one, until you have decided which one you will use.

Start drawing the landscape carefully on the large sheet from your two wash drawings, bearing in your minds eye, roughly, where the huntsman and hounds will appear on the sheet.

For the next few minutes you are now on your mettle, not only as an artist but as a sportsman too. Keep an eye open for the obvious in the sport.

Do not get the huntsman riding over his hounds. I always find it a good thing to keep the hounds well forward.

In depicting the hounds, vary the legs in the action, do not fall into the trap of having too many repetition poses for this, because this is so easily done. Do not have them running haphazardly all over the place, keep them on the line of the fox.

If you can put a favourite old hound in the lead of the pack, do so, it is bound to please your patron and the huntsman too! Follow up with the other seven portrait hounds and the remaining ones will work in casually as the sketch progresses.

Have a loose swinging action with the huntsman and his horse and whilst drawing them refer of course to your working drawings and the ones in your sketch book.

When it comes to members of the field do not have them "riding into the huntsman's pocket". Keep them at their appropriate distance and watch for the many technicalities in connection with the sport that will help at this point.

When satisfied that you are more or less accurate with the pencil state you can safely start work in watercolours.

First sponge over the whole sheet with a wet sponge and leave to dry off a little.

When almost dry, begin by washing in the sky and repeat the same method as when you are sketching on the spot. Have your wash drawings by you and try to get as good a copy as possible as one of the sketches.

Wash over all your hounds and figures with the landscape wash, their outlines will still be visible when the colour dries.

Again put in the trees, fences etc when the paper is dry.

Finally "fill in " your hounds, horses and riders, checking carefully with your coloured drawings and sketch book notes as you do so.

by

Joseph Appleyard

ORIGINALLY

PUBLISHED

in

YORKSHIRE ILLUSTRATED

MARCH 1953

This Article has been augmented with additional relevant material from Joe's Art Galleries

Early this year I was commissioned by one of the joint masters of the Vale of Lune Harriers to paint four pictures of the hunt, the chief one being an oil painting of Alf Stather, the well known huntsman and his hounds.

I well remember leaving Leeds on a Thursday morning. It was January and bitterly cold, sleet and snow were falling, in addition to a biting east wind. Hardly inviting or promising weather for outdoor work at which one must either sit or stand comparatively motionless for considerable periods of time.

I knew I would be treading on hallowed ground, as Turner painted the castle and most of the district round Hornby, in the early part of the last century.

On arrival at Hornby my limbs were stiff and numb, the snow and sleet had changed to torrential rain. The conductor helped me off with my sketching tackle and bade me a hearty good night as he slammed the door of that comfortable bus.

Next morning I made my way with sketching tackle to the kennels, situated on high ground overlooking the castle farm.

Alf Stather met me with a friendly chuckle and a hearty handshake. A keen looking man with shaggy eyebrows, beneath which twinkled boyish-like eyes.

I was then introduced to his wife, a charming, and I should imagine, a most methodical woman. After a brief conversation I went with Alf into the kennels, and on seeing the pack as a whole, I asked him if he would select his best ten hounds. They were soon singled out and mustered into an enclosed yard. These ten were to be featured in the foreground of my painting and this would be the most exacting part of my work for they had to be true-to-life portraits.

Whilst these chosen hounds are running and snooping around I observe more closely the build, pattern, character and action of each hound. When satisfied, I fix up my easel in the adjoining sheltered yard, placing a sheet of paper on the drawing board. Making sure that I have made my dipper of water secure and placing my water-colour box in a handy position, I beckon to Alf to bring in the first hound. The hound dashes in full of spirit and entity, "Hayard" is his name, a nicely patterned black, tan, and white specimen of the pack.

I then sketch him in pencil, freely and quickly on to the paper. After much dashing around (and even much more coaxing by his master to get him to stand in profile) the outline is eventually finished.

My water-colours then come into play and rapidly I wash in the colours, starting probably with the tan colour, then on to black and finally finishing with an opaque white .

"Hayard" is then put back into the kennel and the next hound to be portrayed is brought in. This is a fine bitch hound by the name of "Pansy". The same sketching and painting process is repeated and so on with each hound through the series of ten, "Pilot", "Harmony", "Harriet", "Hilda", "Brenda", "Captain", "Pastime", and "Vera".

"I asked him if he would select his best ten hounds.

They were soon

singled out and mustered into an enclosed yard.

These ten were to be

featured in the foreground of my painting."

The next working drawings are of Alf and his horse. Back in the huntsman's house whilst he is changing into his scarlet coat, Mrs. Stather serves a welcome cup of tea and biscuits. Alf then takes me to the stables. A girl groom leads out his horse, a rather large common-looking bay mare, named Miss Parry. The girl takes off the rug, the mare being already saddled and bridled. I then ask Alf to mount and pose for me, making sure that he is in a natural relaxed position and not sitting bolt upright and stiff which is unfortunately customary when a rider poses for either artist or photographer.

I put another sheet of paper on the board and place it on the easel, making a point of not being too near my models. I take up a position about four yards from them on the near side of the horse. I am now ready to begin.

At this moment I am not interested in the horse, but the position and colour of the huntsman.

I sketch him in on the paper with a pencil and try as much as the small area of space will allow, to get something of the facial likeness. To me, I find this my most difficult task, but having a knowledge of the huntsman' s character helps considerably in getting most of his likeness in the sketch. Taking up the water-colours I perhaps start on his face, and then follow on with, say, jacket, breeches, and boots, and finish with the cap and gloves.

Whilst the artist is sketching he notes whether the rider has a tendency to lean either in a forward or backward position, how the cap fits on the head, how he holds his crop and reins, the position of the boot in the stirrup iron, and how the scarlet coat "swings " over the back of the horse, in fact all the details which the patron is bound to look for in the finished painting.

Next I take up my sketch book and pencil and make a sketch of Alf and the horse, this time to ensure correct proportion of horse and rider.

When this sketch is finished I can let him resume his normal duties, whilst I concentrate on a coloured sketch of the mare.

As the girl holds her, I make a good pencil sketch of the head and bridle. I make close-up drawings of the body, legs, and tail, observing how the mare "carries " her tail.

These drawings are indispensable when doing the finished painting in the studio.

When these drawings have been made in the sketch book, I return to the easel with a fresh sheet of paper on the board. At the same distance as in the first case I take up my position at the easel and again make a careful study in colour. When finished, this completes the artist's day, the sun is just going down, there is a chill in the air. I shiver a little, rubbing my hands, now blue with cold. I have visions of the hotel dining-room with its cosy fire, and a well-earned meal ready served on the table.

With these appetising thoughts I take the sketches, put them into my portfolio, take down my easel and pack my other belongings into my old ruc-sac, feeling content with my day's work.

Alf told me during the afternoon where to go for a suitable background for the painting, and when to take leave of him, he explained in detail how I would get there.

Next morning fortified with bacon and eggs I set out to the hill, south of Gressingham, a village about three miles from Hornby. It was a perfect morning, a hoar frost had settled everywhere and the sun was just breaking through the mist.

I paused at the Old Lune Bridge, and admired the long stretch of country on the eastern banks, which serves as a course for the hunt's point-to-point meeting.

It was ten o'clock when I got to Gressingham, one of the most attractive villages it has been my pleasure to visit in recent years. I branched left from the village, walked on for another mile and eventually came to the scene which Alf had chosen for me. What a grand sight it was! A view commanding, I should think, the best of the Lune and Wenning Valley, with Hornby Castle in the middle distance towards the left.

Alf Stather, the Kennel Huntsman.

A portrait commissioned by one of

the Joint Masters of the vale of Lune Harriers.

It did not take long to rig up my easel and start the sketch in water-colours. It came out as well as I had hoped. Satisfied with the results, I returned to Gressingham and sketched at my leisure near the ancient church, for the rest of the afternoon.

Mr. Everett, the Joint master, had explained that a further two paintings of the hunt were left to my discretion, a third one being of two favourite hunters on the same canvas.

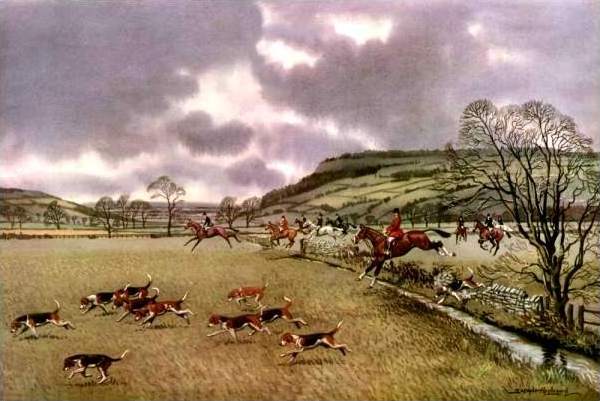

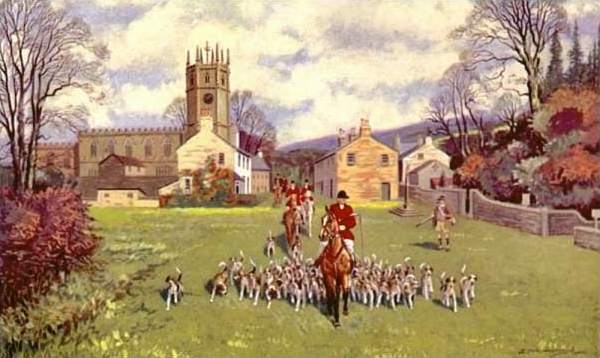

My work was completed for the first of the paintings, the two hunting subjects following in a similar vein during the week, which show hounds in full cry near Aughton and hounds returning to kennel, passing through Hornby village.

The Vale of Lune Harriers in full cry at Aughton Bank

The Vale of Lune Harriers returning to kennel, passing through Hornby village.

I finished off with the material for the hunter portraits.

Mr. Ralph Everett's Hunters

"Willy Wash" and "Columbus"

on the Vale of Lune Harriers

Point-to-Point Course at Whittington, Lancashire.

Mid-January saw me back in Leeds, where in my studio I sorted out the various sketches, putting them into their respective batches. I started on the first of the finished paintings in oils and steadily worked my way onto the others.

I enjoy my work; it is varied and takes me to fresh places - I meet all types of people. As I write now I am reminded of my next commission, which will be in the Holderness country with its vast stretches of flat hunting country, and what is to me, the best thing of all - fresh air!

Joseph Appleyard's

METHODS OF A

SPORTING ARTIST